Table of Contents

Lake Chapo profile

Lake Chapo is a pre-mountain range lake, of glacial origin, located 787 feet above sea level, 25 miles northeast of Puerto Montt and 68 miles southeast of Puerto Varas. It is located between Llanquihue National Reserve and the Andean Alerce Park, but it is not part of either of these two protected areas. It is a one of the lakes that give its name to the 10th Region of Chile -Lake Region. It is the only lake in Puerto Montt commune. Since 1990, it has endured devastating effects of watershed transfer linked to the operation of the Canutillar hydroelectric plant.

Chapo is a Spanish word derived from the Mapudungun native language word Trapen. It can be translated as “connected to”, referring to the proximity between Lake Chapo and Kallfu-ko (or Calbuco) volcano.

Glacial origin of lakes

Lake Chapo would have been “born” at the same time as the glaciation that supposedly led to the formation of Lake Llanquihue, 35,000 to 14,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene.

The first advance of the ice, in this glaciation, would have ended 20 thousand years ago. Therefore, according to this thesis, the geological age of Lake Chapo would be, at least, 20 thousand years.

The geological age of Lake Chapo would be, at least, 20 thousand years.

How are basins formed?

The basins, as natural water-based systems, were formed mostly by natural processes at different times and by the dynamism of the climate, plate tectonics, glaciations and volcanism.

Plate tectonics determines the appearance of our planet’s surface: depressions, mountains, valleys, etc. At the time of glaciations, the ice bodies take over the upper parts of the planet’s surface. The dynamism of climate causes the ice to melt and retreat to the poles: both the solar energy and volcanic activity stimulate a zigzagging movement in these ice masses and large concavities are formed where large bodies of fresh water accumulate forming the basins and, as part of this process, the lakes, rivers and lagoons.

It must be understood three things about the formative process of a basin. First, the result of this process is multiple; several surface and underground courses and bodies of water are formed in parallel, interconnected each other. Second, this dynamic interaction converges to a “point of equilibrium”, whereby the actions of one do not imply the destruction of the other and guaranteeing the continuity of the whole basin system. Third, the biological processes lead to the formation of ecosystems, whose integrity and continuity are tied to the basin system.

The main components of a basin are the main basin or sub-basin (where there is a lake), the tributary river courses that discharge to the main basin, the smaller bodies of water that discharge into those tributary rivers (small lakes located in high places), the benthos zone (where phytoplankton and zooplankton are, among other microorganisms, the base of food chain of the lake ecosystem), the riverside plains where sand accumulates due to erosion processes of ancient rocks, the subterranean layer zone that contain an underground reservoir of water, among other components.

The equilibrium point mentioned above is reduced, in fact, to the fluctuation of the water mirror of the main basin with a variation not exceeding 13 feet (4 meters).

For example, the water mirror of Lake Chapo since 1944 to 1983 varied from 794 feet (242 meters) above sea level in rainy winters to 784 (239 meters) above sea level in dry summers, according to Endesa electric company’s records. Usually it was located at 787 feet (240 meters) above sea level, its historical average level. This natural fluctuation of the water mirror of a lake is called the equilibrium point of the basin.

Lake Chapo basin

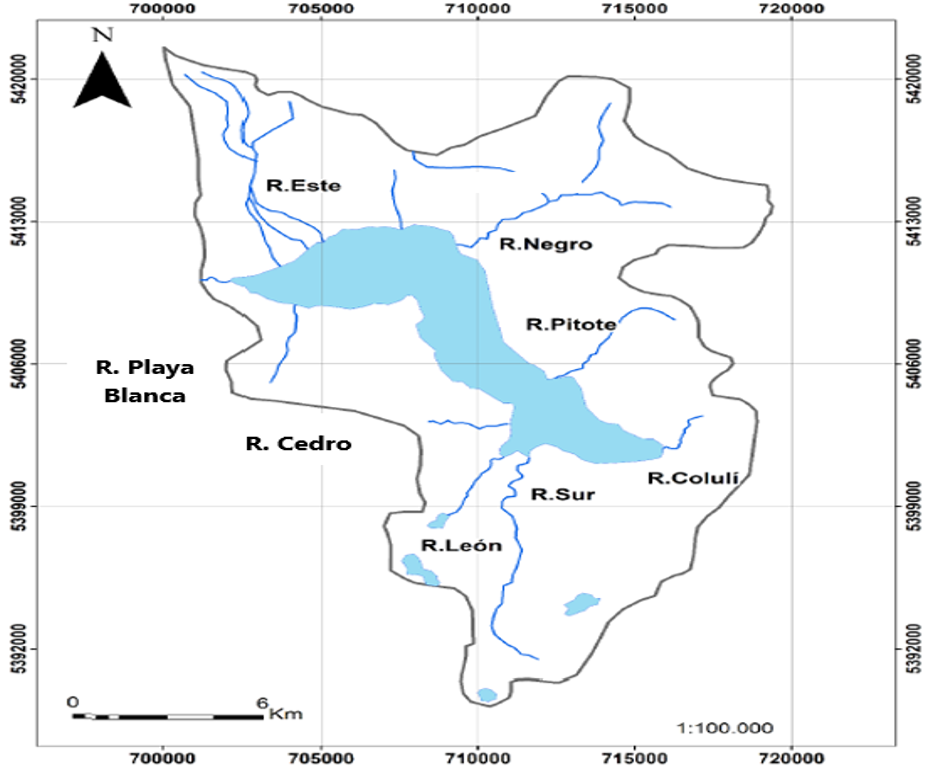

Lake Chapo basin is made up of eight main tributaries. Linked to some tributaries there are a dozen minor lakes and mountain lagoons, presumably of glacial origin and possibly formed in the same geological process that led to the main basin.

In the zone of Alerce Andino park are located the minor lakes Campaña, Montaña, Tronador, Verde, Gaviotas, Escorpión, and others. As distinctive feature, these minor lakes (known as mountain range lagoons) are next to evergreen tepu and larch forests. It is usual to find mountain lagoons surrounded by ancient larch trees and, in some cases, connected to wetlands where new larch trees grow.

The Montaña lagoon, for example, flows into the Campaña lagoon, the latter discharge into the León river and the river into the lake Chapo, forming a system of water cups, one of the few in the area. The Tronador lagoon, circular in shape, in turn flows into the Tronador river, which also flow into lake Chapo.

Under normal conditions, that is before the Canutillar plant bursting in, Lake Chapo flows west, as most of the country’s basins.

Until 1990, Lake Chapo drained through its northern shore, giving shape to the Chamiza river, which (fed by minor tributaries) until today irrigates the Chamiza valley, 19 miles long (30 km).

In short, the Lake Chapo basin is a water system of glacial origin formed at least 20 thousand years ago. Its formative process would be closely linked to the formation of several other minor wonderful lakes or lagoons in Andean Alerce Park. It has eight main tributaries, some linked to mountain water bodies, the minor lakes mentioned above.

Lake Chapo basin, like the vast majority of national basins, carried fresh water to the sea, flowing west. This movement was interrupted in 1990, when the Canutillar hydroelectric plant “burst in”.

In following articles we will delve into this and other aspects of Lake Chapo.